Monday, September 12, 2005

(Das Kabinett des Doktor Caligari)

Directed in 1919 by Robert Wiene, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is the story of murder and intrigue set in a small German town of Holstenwall. Francis (Friedrich Feher), our narrator, is a student who makes the near-fatal error of attending a carnival with his best friend, Alan (Hans Heinrich).

At the fair, our two lads decide to visit the stand of Dr. Caligari (Werner Kraus), an embittered small man who advertises a somnambulist by the name of Cesare (Conrad Veidt - dressed head to toe in black. My hero!) Cesare, prodded from his slumber, answers Alan's burning question: "How long will I live?" with: "You will die tomorrow" (hey, ask a stupid question...)

Coincidentally, Alan is murdered that night.

Now Francis, no fool, figures things might not be on the up-and-up with the good doctor and his sexy black-clad accomplice. He visits Caligari's house and sees the kindly sight of Dr. Caligari feeding Cesare broth. Hardly anything incriminating. More to the point, with Alan out of the picture, Francis now has exclusive dating rights to the beautiful Jane (Lil Dagover).

Meanwhile, another Holstenwall murder has occurred and Jane's father, Dr. Olsen (Rudolph Lettinger) has disappeared. Jane decides to visit the fair to see if she can find clues to his whereabouts. Oddly enough, the only booth that seems to be open is that of Dr. Caligari. Caligari invites Jane in and shows off his prize possession, Cesare in the coffin. They both ogle her for a while before she leaves in horror (took her long enough). And, since it is a silent film, Dr. Caligari and Cesare never really talk to her - they just sit and stare with their fantastically made-up eyes. Strange, eh? And they never answered her question about dear old Dad...

Later that night (avoid night at all costs in horror films), Cesare rises from his coffin and starts stalking Jane with a shiny knife. Wait a minute! That was the weapon used to kill Alan! The suspense thickens... Jane wakes up and is understandably upset to see this skinny guy in a black unitard standing over her with a knife while she sleeps (although, since it's Conrad Veidt, no one feels too sorry for her). She faints and is now totally at the whim of Cesare, a guy who's already killed one of her lovers. Nice going, Jane!

Lucky for her, Cesare falls in love with her prone form and refuses to kill her. In good old monster movie fashion, he throws her over his shoulder and heads for the hills. Unfortunately, the movie takes a surprisingly literal turn - Cesare suffers a massive heart attack from carrying Jane, drops her, and takes a headlong plunge down the mountain, splatting on the bottom. Sniff. No more Cesare.

The townsfolk finally catch up with Jane (somehow a thin guy carrying about 130 lbs of dead weight managed to keep ahead of them on the narrow, rocky incline. The townsfolk aren't too useful). Jane has survived the ordeal marvelously and is eager to head to town to condemn Dr. Caligari. Once in town, Jane and the townsfolk run into Francis, who insists that it couldn't have been Cesare who kidnapped Jane - he's been spying on the Caligari house and has seen Cesare sleeping the night away, under Dr. Caligari's watchful eye.

Jane, who's beginning to suspect that Francis is a schmuck, insists that it was Cesare who abducted her. The townsfolk run over to Caligari's house, throw open the coffin and remove the clever stuffed dummy that Dr. Caligari placed there while Cesare was on his killing spree (hey, it fooled Francis). Dr. Caligari takes advantage of the townsfolk's ignorance once again, and escapes while everyone is looking at the dummy (Cesare, not Francis).

Francis, who seems almost astoundingly incompetent, decides to find Dr. Caligari on his own. He reasons that the Doctor might have escaped from an insane asylum, so he pays a visit to the local one (right near the carnival - groovy!), where the interns tell him that he'll have to see the head honcho. They send him upstairs to meet (dum-dum-dum)...

DR. CALIGARI!!!!

Dr. Caligari is the head of the insane asylum! He fooled them all! Francis - Jane - the townsfolk! They probably should have paid more attention to the "Dr." part of his name. Francis manages to back out of the office hurriedly, and Dr. Caligari is kind enough to pretend he doesn't recognize Francis.

Later that night, Francis returns to the asylum and reads through Caligari's journals (hey, what's a little invasion of privacy between friends?)

Turns out, there was a mountebank named 'Caligari' in 1612, who ran around with a somnambulist that he trained to commit murder. Our Dr. Caligari thought it would be a good test (he's a doctor, you see) to see if he could make a patient of his commit murder. As luck would have it, Cesare was admitted to his asylum at the same time. So Caligari threw away the profitable, safe career of Head of the Asylum and took on the more garish, flashy dress of circus performer\murderer. And succeeded nicely. Until now.

Meanwhile, the townsfolk have found Cesare's corpse and brought it back to the asylum (and they think Caligari is sick? Sheesh - at least he wasn't exhuming corpses for laughs). Dr. Caligari eventually awakens and is bummed to see Cesare lying dead, propped up in his office. Caligari weeps over Cesare while the attendants gleefully handcuff their former employer and toss him in a cell (which leads me to wonder who they're planning on having sign future paychecks).

Good triumphs over evil! Francis saves the day!

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Odder still, the story isn't done here. The above portion was, more or less, the story that Hans Janowitz and Carl Mayer wrote (being somewhat disgusted with people in power at the time). Fortunately, everyone loved the story. Unfortunately, the story was altered and a framing device was added. The framing device goes something like this:

Francis is sitting with an odd, old man on a bench. He sees a spacey Jane walk by, which reminds him of a story...

The complete story is inserted here.

Once Francis completes his tale, they return to the asylum where they see Cesare alive, gently stroking a flower and Jane off in la-la land, pretending that she's a queen. Dr. Caligari comes down the stairs, and Francis goes wild ("That's the guy I was telling you about! Arrest him"). The attendants grab Francis instead, suit him up with a form-fitting straight jacket, and throw him in one of the handy cells.

Dr. Caligari removes his glasses, looking more kindly than he has all movie, and muses "Strange, he thinks I'm Dr. Caligari. But he will be cured. Now that I know his problem, he'll be cured."

I believe the nicest thing about the framing device (which appalled the original writers, as it was never their intention to portray Dr. Caligari in a kindlier light) is its ambiguity. For example, we never *do* see Alan's original murderer. Is it possible that Francis killed Alan and blamed the murder on Dr. Caligari? He did win Jane the flake, afterwards, and murders have been committed for much less.

Furthermore, I'm none too sure that the kindly doctor isn't planning a "permanent" cure for Francis....

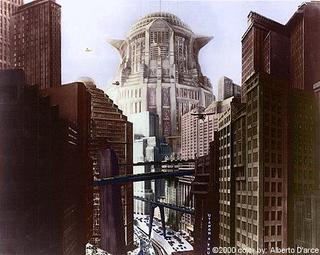

Fritz Lang's Metropolis

Lang, Fritz (1890-1976), was an Austrian-American film director. He made more than 30 films in Germany and the United States, his first successful one being Der müde Tod (Weary Death, 1921), issued in the U.S. as Between Worlds. Lang's masterpieces include Metropolis (1927), (Kaplan 232) in which a magnificent futuristic city is maintained by workers enslaved underground; M (1931), his first sound film, a psychological thriller about a compulsive murderer; and two studies of the criminal mind, Dr. Mabuse (1922) and The Last Will of Dr. Mabuse (1933). (Kaplan 432) The latter won the approbation of Nazi officials who sought Lang's collaboration. Lang, who was half Jewish, fled Germany immediately; he became an American citizen in 1935. Among his films made in the U.S. were Fury (1936), about a lynch mob; You Only Live Once (1937); Rancho Notorious (1952); and Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956). (Kaplan 12)

Lang's early architectural and art training is evident in his visual approach; he developed narrative and created an atmosphere through expressionistic, symbolic sets and lighting, as well as through his editing. Just as conventional lines and shapes are distorted in traditional German expressionism, Lang’s futuristic cityscapes are distorted.

Even though Fritz was from Austria, his works are studied as German cinema. The striking and innovative German silent cinema drew much from expressionist art and classical theater techniques of the period . The most celebrated example of expressionist filmmaking of the time is The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919) by Robert Wiene, in which highly stylized costumes and settings were used to tell the story from a madman's point of view. A similar concern with the supernatural is evident in such films as The Golem (1920), by Paul Wegener, the vampire film Nosferatu (1922), by F. W. Murnau, and Fritz Lang's science fiction spectacle Metropolis (1926), which deals with a robot-like society controlled by an evil superindustrialist. (Kaplan 43)

By the mid-1920s, the technical proficiency of the German film surpassed any other in the world. Artists and directors were given almost limitless support from the state, which financed the largest and best-equipped studios in the world, the huge Universum-Film-Aktiengesellschaft—popularly known as UFA—near Berlin. (Kreimeier 32) Introspective, expressionist studies of lower-class life known as “street” films were marked by dignity, beauty, and length, displaying great strides in the effective use of lighting, sets, and photography. German directors freed the camera from the tripod and put it on wheels, achieving a mobility and grace never seen before. Films such as Murnau's The Last Laugh (1924), starring Emil Jannings, and The Joyless Street (1925), by G. W. Pabst, starring the Swedish-American actor Greta Garbo, were internationally acclaimed for their depth of feeling and technical innovation. Because of the immigration of the best German film talent to America, including the directors Murnau and Lang and the actor Jannings, German films declined quickly after 1925, becoming imitations of Hollywood productions.

Since Lang is a self-proclaimed, “visual person” German expressionism was the perfect style for him to work from for his epic science fiction film, Metropolis. (Atkins 19) This 1926 silent, tinted film relies on innovative visual imagery that was well ahead of its time. Metropolis was produced by UFA (Universum-Film-Aktiengesellschaft), directed by Fritz Lang, and his wife Thea Von Harbou. Cinematography was by Karl Fruend and Guenther Rittau. The Production Design was by Otto Hunte, Erich Kettelhut, and Karl Vollbrecht. The fantastically creative costume design was the work of Aenne Willkomm. Metropolis was produced by Erich Pommer. (Parish 225)

The story takes place in 2026, one-hundred years from when the movie was made. The world Von Harbou and Lang created was a cold, mechanical, industrial one. Since this movie was produced not long after the industrial revolution, it could be a foreshadowing of what the world would have been like if the industrial revolution had kept growing. The city of Metropolis is a crowded one where people are either of the privileged elite, or of the repressed, impoverished masses. Vast numbers of the lower class live underground to run the machines that keep the above ground Metropolis in working order. The workers run the machines, but the machines run the lives of the workers. The monotonous droves of workers are truly a, “mass of men leading lives of quiet desperation,” to quote Thoreau. Lang portrays this with a montage of cattle-like herds of people, grinding machinery, and clocks.

In contrast, the other portion of this futuristic world plays and delights in the gardens and stadiums. The scene that illustrates this shows an orange stadium with blue sky drifting by as the privileged class enjoys Olympic-style races. This is when we meet one of the main characters, Freder Fredersen, played by Gustav Froehlich. Later we see Freder frolicking with a girl in the Eden-like Eternal Gardens of Pleasure. As Freder flirts with the girl at the fountain, he sees Maria emerge. Maria, who is played by Brigitte Helm, is dismissed as the daughter of “some worker” by others, but Freder is quite taken by her. Freder pursues her into the foreign Underground City.

In the Underground City, Freder sees an old worker struggling with the dials on a piece of clock-like machinery. The worker fails to keep up with the demands of the machine, and thus the machine blows up. Freder begins to hallucinate that the masses of workers are being shoved into the mouth of the monstrous machine. The imagery of Metropolis’ unquenchable hunger for more human lives is symbolically clear. Lang’s visual talents are apparent.

Freder, who is astonished by the horror of the Underground City, rushes to talk to his father. On his way there, the viewer gets a tour through Metropolis. Lang visually shows how cold, crowded, busy and yet beautiful Metropolis is. Futuristic paintings and models of the city show the unique architecture as well. The freedom science fiction lends to a visual director is limited only by the director’s imagination. Suspended streets, and zig-zagged building, only begin to exemplify the bustling city. It is obvious how influential Metropolis has been on later science fiction films when one looks at a movie like Blade Runner. The cityscapes created for Blade Runner look like an updated version of Metropolis.

When Freder reaches his destination, we see that his father is Joh Fredersen, the Master of Metropolis. Note how he is called the master, and not the leader of Metropolis. This says a great deal about the character even before we know much more about him. He rules and dominates the city, not directs it. Joh, who is played by Alfred Abel, is a frightening combination of (Shakespeare’s) Richard the III and Hitler. The Hitler allusion is particularly alarming considering the concentration camp-like imagery used in the Underground City scenes, and the fact that this film was produced in pre-Hitler and pre-World War II Germany. Joh’s character also has the biblical parallel of the Egyptian pharaoh enslaving the Jews to build pyramids. In fact, when Freder arrives, he asks his father,” Why do you treat the workers so badly?” Joh replies that it was, “their hands that built Metropolis!”(Lang)

Later on, Freder once again ventures down into the Underground City. Freder visualizes the worker struggling with the dials, and the image of a clock bleeds through in a dissolve. Hard work, machine-like efficiency, and time are expressed in this effective sequence of images. Freder remembers what happened to the last poor, struggling worker and goes to help this one. Freder volunteers to “trade clothes and identities” and work the machine for the man. Freder tells Georgy the worker to give a message to his friend Josephat. Georgy goes to deliver the message, but is side tracked by the red-light district of Metropolis, to a place called Yoshiwara. Josaphat does not receive his message.

The next scene introduces the viewer to an old, rickety house owned by Rotwang, an inventor and scientist. He is consumed by the memory of an old flame named Hel. It turns out that there was a bit of a love triangle between Rotwang, Hel, and Joh. Joh ended up marrying Hel, and she died while giving birth to Freder.

Joh wanted some secret worker plans deciphered by Rotwang, but Rotwang had something more significant to show Joh. Rotwang presents Joh with his new invention, a strikingly beautiful robot that is suppose to be Hel. Rotwang exclaimed, “All it is missing is a soul!”(Lang)

Meanwhile, Freder comes across a copy of the worker’s plans, and a co-worker comes over to confide in him that, “Maria is having another meeting.” In anticipation of seeing Maria again, Freder works away at the dial. Visual images of the dials on the machine and the clock merge back and forth. Fritz makes it clear that the work is painstaking, the shifts are long, and time does not seem to go fast enough when waiting for the shift to be over with.

Finally, the shift does end and the workers file down into the deep catacombs to see Maria speak. The biblical theme reoccurs again. Maria is named after the Virgin Mary, she is speaking at an alter with crosses on it, and the workers are in the catacombs with her. The catacombs are where the ancient Christians used to hide out and worship when seeking refuge from prosecution for their beliefs. Freder collapses to his knees as if worshipping Maria. Such visual analogies seem to be the simplest way for Fritz Lang to explain concepts without words.

Maria tells the workers the story of the Tower of Babel. The parallel is made between the slaves who built Babel, and the workers who built and maintain Metropolis. A image of thousands of chained, bald, slaves is presented. They are treated like livestock as they are herded off to work. The disturbing concentration camp images are alarmingly prophetic.

In Maria’s oration, she talks about how the conceivers of Babel did not care about the slaves. The conceivers of Metropolis do not care about the workers. Both places need a mediator between those who rule, and those who are ruled.

Meanwhile, Joh and Rotwang witness Maria’s sermon because the deciphered plans led them to her. Joh tells Rotwang to make the robot look like Maria. Joh believed that if he had a duplicate of Maria that he would have control over and could manipulate the workers. He would have a very powerful tool.

After the sermon, Freder and Maria kiss for the first time. Maria tells him to meet her in the cathedral tomorrow. Freder leaves, and Maria is alone in the catacomb. Rotwang comes out of his hiding place and pursues Maria. He chases her with a flashlight, corners her, and captures her. Freder never met Maria at the cathedral. Freder finds out where Maria is when she shouts through a grate in the street while trying to escape Rotwang. Freder tries to save her, but she is swiftly taken away to the laboratory.

Maria is hooked up to a myriad of machines and contraptions, and so is the female robot. This scene is a visual cacophony of special effects. It a showcase of creativity for Fritz Lang. Glowing rings and lightning effects flash as the robots face dissolves into Maria’s face. This is a creation scene right out of Frankenstein. (Menville 34) The new robot Maria is an evil, lusty character unlike the pure, angelic real Maria. Brigitte Helm makes this apparent by portraying the robot with one eye more open than the other to give her a devilish look.

Rotwang brings robot Maria to a party at Yoshiwara’s to show Joh how real she is to everyone else. The robot gets up on stage and does a tempting, nude, Salome style dance. At which point, Lang cuts to a montage of lecherous male eyes.

The feverishly sick Freder senses this dance in a hallucination and is distraught. He then hallucinates about the Seven Deadly Sins statues he saw in the cathedral. In the vision he sees the Grim Reaper swing his scythe. Once out of his fever induced haze, Freder finds out where Maria is and sees her out. He goes to Yoshiwara’s and finds the robot Maria.

Eventually, the robot Maria gives a diluted sermon to the workers. It ill advises her followers to take up violence, not peace. Freder realizes that this is not the real Maria. Maria leads the masses to the machines in the Underground City and orders them to be destroyed. The workers did not know that destroying the machines would flood the area and drown their children. The machines are bound by the people, and the people are bound by the machines.

In the meantime, the real Maria escaped Rotwang and witnessed the failure of all the machines. The water ruptured through and flooded the Underground City. Maria worked with the machinery to try and stop the flooding, and gathered the children in an attempt to keep them safe. Eventually Freder finds Maria, and together they stop the flooding.

At one point Joh watched the city of Metropolis from his high-rise office. All one sees is Joh sitting at his seat, looking at something out of the shot. The wall behind him shows the reflection of lights blinking. The light is coming from the city which we cannot. When the office goes still and dark, it is implied that Metropolis is “broken.” This is a very effective visual effect of Fritz Lang’s. There is no need to see the city, we know it is there.

In the Underground City, the workers think that Maria has tried to drown their children. They workers go on a witch hunt after Maria. The workers think she is at Yoshiwara’s, and there they find the robot Maria celebrating the fiasco she has created. They capture the robot who is laughing wickedly, and they tie her up to burn her at the stake. In the confusion, Freder thinks the real Maria is being burned. The workers eventually see the robot beneath the burned away flesh. Freder realized that he must find the real Maria again, and he finds her trying to escape Rotwang who is chasing her. Rotwang and Freder fight on the roof top of the cathedral. Rotwang ends up falling to his death.

The masses march into the church, and they realize that Freder is the mediator they where seeking. They found the midway point between Joh and the workers; the ruler and the ruled.

Since the initial spark of Melies Trip to the Moon, science fiction has been welcomed by cinema. Yet Trip to the Moon was just 1800’s spectacle stage, it was not a full-fledged science fiction masterpiece like Metropolis.(Menville 18-20) The pioneering effort that Lang took on has and will affect science fiction film for generations.

SAMPLE RESEARCH PAPER

Fritz Lang's silent film Metropolis, produced in 1927 in Germany, paints a picture of a horribly polarized future society in which the workers toil like cogs in a machine while the rich live a lavish lifestyle in their towers high above the overpopulated city. The film itself is steeped in expressionist imagery which emphasizes the emotional quality of the plot that develops. As a whole, the film serves to reflect Lang's vision of a technologically dependent society and in turn comments upon the industrialization of his homeland.

Many German films produced during the early 20th century were influenced by expressionism, most notably Robert Wiene's 1920 film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. While Metropolis may not carry as much overt expressionistic imagery as early films like Caligari, its themes are much more similar to the spirit of expressionism (1). That is not to say that Metropolis lacks expressionist imagery -- in fact, many scenes, such as the opening sequence of the film, are heavy in expressionist imagery.

Fritz Lang's Metropolis takes place in the dystopian future of the the year 2026 (a distant 100 years after the film's creation in 1926-7). The city itself has been devided into two parts -- the upper city, habited by the wealthy ruling class, and the lower (underground) city, populated by the poor working class. The lower class spend much of their day toiling on the enormous machines that keep the city running, living a mostly dismal existance.

One day, a young man named Freder (son of Joh Fredersen, ruler of the city Metropolis) loses his way chasing after a girl and ends up in one of the machine rooms of the lower city. He witnesses an acident at one of the large machines and envisions it as a demonic beast (at one point, he exclaims "Moloch!" in horror). After witnessing this accident, he returns to the upper city to tell his father about what he has seen.

Joh is, of course, pretty much indifferent to his son's emotional reaction to what has happened. Freder now feels a sense of obligation to help the workers of the lower city and returns to the machine rooms. He offers to take the place of one of the laborers at one of the machines and subsequently struggles to keep up with the frenetic pace of the machine. Meanwhile, Joh Fredersen has a meeting with the mad scientist Rotwang. There he sees Rotwang's latest invention, a robot that will some day replace the workers in the machine rooms. Later, Rotwang takes Fredersen to observe one of the workers' secret meetings (unbeknownst to Rotwang and Fredersen, Freder is also at this meeting) run by Maria, who gives the workers hope. Rotwang explains that he will capture Maria and create his first robot in her image so that he can twart their uprising.

Rotwang is successful in capturing Maria and transferring her appearance to the robot. Freder tries to save Maria, but by the time he arrives at the laboratory, the procedure has already taken place and he discovers the robot Maria (who looks just like the real Maria) conspiring with her father. Thinking Maria has betrayed him, he leaves. The robot Maria then incites the workers to revolt prematurely, ensuring their deaths so that they can be replaced by robots. The workers destroy some of the machines, causing a flood that will eventually drown them all if they are not saved.

Eventually, the real Maria escapes and she and Freder help save the workers from the flood. The workers then find the robot Maria and burn her at the stake, at which point she transforms back into a metallic robot, giving the workers reassurance that they have done the right thing. The movie ends with the death of Rotwang and a change of heart for Fredersen, who now feels compassion for the workers.

The opening sequence to Fritz Lang's Metropolis serves to define the class structure that dominates the film. The film begins with a short title sequence, then shows some abstract imagery of machinery at work. We are then shown a few slow-paced shots of one shift of workers marching out of the elevators and a new shift marching on to the elevators. In stark contrast to this is the next scene, in which Freder (the main character and eventual hero of the story) is shown playfully running around a large, elegant fountain surrounded by young women, chasing after a particular girl and finally catching her. These scenes are used to establish the theme of the upper vs. the lower class that pervades the film.

In Metropolis, there are two well-defined classes -- the working class and the upper class. Not only are the roles of these two classes extremely different, but so are their daily routines, which are both shown in the sequence, are as well. While the working class spends its days toiling amongst the machines below the city, the upper class lives an opulent existence high above the city. This use of two establishing shots with completely different narratives helps define the stark difference between these two classes. This theme of class difference was very important to the expressionist movement.

Perhaps the most obvious expressionist means employed by Lang is the use of lighting and contrast. When the workers are shown drudging in and out of the elevators, the lighting is dark and the contrast is heavy. This darkness reflects the dismal nature of their lives as laborers. On the other hand, Freder and his female companions are elegantly lighted and the contrast is in the scene is soft and light. The image presented is much more visually appealing than that of the downtrodden workers.

· The Downtrodden Workers

· The Opulent Garden

As the film progresses, this theme of the dark, downtrodden workers being juxtaposed against the opulent upper class is incredibly important to the unfolding of the plot. These establishing scenes of the two classes are crucial to the narrative that later unfolds. By defining the classes so objectively, Lang makes it easy for us to understand how someone like Freder could be so horrified by them.

By the time Metropolis was released in 1927, expressionism was no longer part of the avant-garde (1). An expressionistic influence can be seen, however, throughout much of the film. The plot of the film, as outlined earlier, adheres to the expressionist tradition. Expressionist influences can also be seen in the acting, imagery and set design of the film.

The exaggerated movements of both Rotwang and Freder owe much to the expressionist theatre. Freder becomes the moderating heart between the workers and the upper-class and his exaggerated, whimsical movements reflect this (2). Rotwang, on the other hand, plays the role of the archetypal mad scientist. His movements are jerky and overstated, reflecting his manic state of mind (3).

Direct parallels can be seen between the expressionist drawings of Max Beckman and George Grosz, and Lang's portrayal of the lower-class in Metropolis. Take, for example, Beckman's Figures and Grosz' The Hero, two exaggerated depictions of lower-class subjects. These drawings closely resemble the dirty, downtrodden lower-class workers that toil in the underground city of Metropolis.

· The Hero (George Grosz, undated)

· Figures (Max Beckman, 1915)

· Metropolis lower-class workers

Another example of where Metropolis mirrors expressionist art is in the angular, crowded skyline of the city. Expressionists were concerned with the role of the city in a modern, industrialized world. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's Red Tower in Halle is an excellent example of the stylized, angular urban view of the expressionists. The tower in the foreground of this painting resembles the tower at the center of the city of Metropolis.

· Red Tower in Halle (Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, 1915)

· Metropolis skyline

Metropolis also draws influences from early German expressionist cinema, especially in its lighting. While many of the scenes that take place in the upper city are lit in a fairly traditional way, the scenes that take place in the underground city are full of the shadows and bright, angular lights that filled early expressionist films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. This use of lighting (much like the use of many other expressionist techniques) serves to further emphasize the expressionist themes present in the plot of the movie.

· Screenshot from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

· The underground city in Metropolis

Many film scholars do not consider Metropolis to be an expressionist film. When it was created, the expressionist movement was no longer happening. By 1927, the social and political climate in Germany had changed. In fact, at the time, Metropolis was the most expensive motion picture ever produced. Although it may not be a true "expressionist film", the influence that expressionism had on Metropolis can not be ignored.

· Metropolis

· Fritz Lang

Barlow, John D. German Expressionist Film. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1982.

Darlow, Luke. Metropolis Multimedia Archive.

Eisner, Lotte H. Fritz Lang. London: Secker & Warburg, 1976.

Elsaesser, Thomas. Weimar Cinema and After: Germany's Hisorical Imaginary. New York: Routledge, 2000.

1. Barlow 123

2. Barlow 124

3. Barlow 125

Metropolis Walkthrough

Visit the City of the Future of the Past

Inspired by the movie Metropolis by Fritz Lang

Enter the Walkthrough

View Character Profiles

The following films are all from the same genre and are very similar to each other.

Although made at different times, one can see the great influence that the original

Metropolis (1926) has over its descendants. Which version of the film do you feel

is the best and why?

Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1926) vs.

Ridley Scott's Blade Runner (1982) (Sci Fi /Narrative/ Film Noir) vs.